Table of Contents

For the failure of Christopher Columbus to find China or India, Spain quickly found ample compensation in the wealth of tropical and semi-tropical lands scarcely realized by primitive native races and awaiting exploitation by Europeans. Colonization of the new lands followed discovery so closely as almost to be simultaneous; thus, Columbus founded a colony at Navidad, Hayti, on his first voyage. On his second voyage he commanded a fleet of seventeen vessels, carrying 1500 persons, and founded two colonies. Romantic tales of conquistadors like Hernando Cortez and Francisco Pizarro yield in human interest to the story of the building of a New Spain in America, the rise of commercial cities, the spreading of European culture in a more luxuriant setting in the new world than on the bleak plains and rugged hills of Spain, the establishment of missions and churches, schools and universities, and the setting up of printing presses, books, pamphlets and maps from which are counted among the most precious possessions of Brown University in the John Carter Brown Library of Americana. Within the present United States, St. Augustine in Florida, 1565, and Santa Fe in New Mexico, 1605, were founded by Spaniards. The second half of the sixteenth century witnessed three failures by the French Admiral de Caligny to establish Huguenot colonies in America, and likewise the failure of Raleigh’s colony at Roanoke Island. The French were successful at Port Royal, 1604, as were the English at Jamestown, 1607, and at Plymouth, 1620, and the Dutch at New Amsterdam, 1626. With the Puritan settlement at Massachusetts Bay in 1630 a great migration from England westward was in full swing. Dr. James Truslow Adams, in “The Founding of New England,” estimated the total of English emigration in ten years preceding 1640 as having exceeded 65,000, of whom perhaps 18,000 were in New England as follows: Massachusetts, 14,000; Connecticut, 2000; Maine and New Hampshire, 1500; Rhode Island, 300. The fishery at Newfoundland, active since 1500, attracted 10,000 fishermen six months of the year. The presence of fishermen along the coast of New England explains the “wrought copper” ornaments worn by the Indians and described by Verrazzano, the bronze-tipped arrows found by the Pilgrims among those in use by Wampanoags in 1620, the “welcome” in English extended to the Pilgrims by Samoset as he marched down the village street at Plymouth in the spring of 1621, and the fluency in English of Squanto, the Indian interpreter and guide of the Pilgrims. That there were economic causes for the great English migration paramount to the religious causes alleged as the reason for some part of the movement is disclosed by careful study. The failure of Massachusetts to permit liberty of conscience, in a colony alleged to have been founded to secure liberty of conscience, is somewhat less inexplicable if the migration of the Puritans is studied from the point of view of economics. In this field there is no more informing work than the “Founding of New England.”

The type of fishing village that was not uncommon along the coast of what is now Maine even before the Pilgrim settlement at Plymouth in 1620, and that induced Henry Sweetser Burrage to maintain that Maine rather than Massachusetts was scene of the earliest English permanent colonization in New England, appears not to have been established in Rhode Island, although it is not unlikely that Narragansett Bay was visited occasionally by the hardy fishermen who sought on this side of the Atlantic sea food for European markets 3000 miles away. The Dutch West India Company established a trading post at Dutch Island so early as 1625, having purchased from the Indians the island which they called “Quotenis,” near the “Rhode Island,” and two other trading posts in what is now Charlestown. Abraham Pietersen was the factor at Dutch Island. The Indians, in April, 1632, attacked a house at Sowamset, now Warren, which was occupied by three men as a temporary trading post. Yet there was no permanent white settlement in Rhode Island until 1634, when William Blackstone sold his land in Shawmut, Boston, purchased cattle, and removed to Study Hill, in Cumberland, near the river which still bears his name above the falls at Pawtucket and from its source in Massachusetts. Blackstone had lived some ten years in Shawmut, anticipating by five or six years the Puritan settlement. He was a clergyman of the Church of England, who had left England, and like so many others subsequently, left Massachusetts for conscience’s sake. He is reported as having said, “I left England to get from under the lord bishops, but in America I am fallen under the power of the lord brethren.” He maintained friendly relations with the Puritan settlers, nevertheless, and visited Boston, as well as Providence occasionally. He is said to have planted the first orchard in Massachusetts, and also the first apple orchard in Rhode Island. A seventeenth century forerunner of Luther Burbank, “he had the first (apple) of that sort called yellow sweetings that were ever in the world perhaps, the richest and most delicious apple of the whole kind.” To “encourage his younger hearers” when he preached in Providence he “gave them the first apples they ever saw.” William Blackstone continued living at Study Hill until his death, May 26, 1675. The Blackstone house and library were burned by Indians during King Philip’s War. Study Hill was leveled in the nineteenth century to make way for the railroad yard near Valley Falls.

William Blackstone had led the life of a recluse; he was a man of scholarly disposition and habits, who found a solace for his discontent with human society in the seventeenth century in the brooding solitude of the wilderness—at Shawmut, first, where with his family he lived alone until the coming of the Puritans brought him neighbors and a kind of meddlesome neighborliness that soon aroused anew his discontent, this time with the “lord brethren,” and, later, at Study Hill, where he was sufficiently and satisfactorily so far removed from intruding companionship as to live contentedly for the forty years that preceded his death. Neither he nor William Arnold, of whom it is alleged that he and his family removed from Massachusetts to that place which is now called Providence on April 30, 1636, two months earlier than Roger Williams, was the dominating influence in the establishment of Providence Plantations or Rhode Island. In the instance of neither Blackstone nor Arnold was there fact or episode so transcendental as to give to either more than an incidental mention in history. Nor was it the success of Roger Williams in the organization of a commonwealth, for of this there remains a question to which attaches a reasonable doubt, so much as his defence and maintenance against tremendous opposition of principles of human liberty and justice, that have given him enduring renown that grows with the ages, and that have made the history of Rhode Island significant for America and for all mankind.

Roger Williams Settles

In June, 1636, Roger Williams, with one, or perhaps several, companions paddled a canoe down the Seekonk River, around India Point and Fox Point into the Providence River, and thence into the Moshassuck River, and on the easterly bank of the last, near and convenient to a spring of fresh water that still flows and has since then borne the name of Roger Williams, began a settlement to which he gave the name Providence in recognition of and thankfulness for the Providence of God, which had guided him Ihis was the actual beginning of Providence Plantations and of Rhode Island; it had antecedents that require retrospect into the causes that had induced Roger Williams to venture thus into the Indian country, as well as consequences that made history.

Roger Williams was born, probably in London, in 1603, son of James Williams, a merchant tailor, and of Alice Williams, born Alice Pemberton. The date of his birth is given otherwise variously as 1599 1601, 1604 and 1607; and the place of his birth as Gwinear in Cornwall, and as Maestroiddyn in Wales. The confusion as to identification arises from the facts (1) that there were two other persons of distinction who were born at the same period and named Roger Williams; (2) that Roger Williams had a brother, named Robert Williams, who was a resident of and teacher at Newport, for whom he has been mistaken probably because of the somewhat similar sound of the names, and (3) that there was also at the period a man named Roderick Williams living in England. Rejecting a probably erroneous identification with a man named Williams, who was graduated from Oxford University, it appears that Roger Williams, founder of Providence Plantations and Rhode Island, was in his youth a shorthand reporter of the proceedings before the Court of Star Chamber, and there drew to himself the attention and patronage of Sir Edward Coke, who was afterward Chief Justice of England. Sir Edward Coke sent Roger Williams to Charter House to be prepared for college, and Roger Williams was graduated from Pembroke College in Cambridge University in January, 1626-1627,[1]January, 1626, Julian calendar, old style; January, 1627, Gregorian calendar, new style. The Gregorian calendar made January, instead of March, the first month. with the degree of Bachelor of Arts. In recognition thereof the first building constructed exclusively for the Women’s College in Brown University was named Pembroke Hall, and when, in 1928, the Women’s College became a distinct unit in the University, it was named Pembroke College.

Sir Edward Coke intended to prepare Roger Williams for jurisprudence; the latter forsook law for theology, and was ordained in the Church of England. Later he rejected preferment and promotion in the Church of England, and became a non-conformist of pronounced type. Not an adherent of the Puritan party in England, he found himself not in harmony with the Puritan party that controlled the identical civil and ecclesiastical organization of the theocracy in Boston; he appears to have been closer in doctrine to the Pilgrims of Plymouth than to the Puritans of Massachusetts. It has been suggested that Roger Williams did not know when he sailed from Bristol, England, December 1, 1630, on the ship “Lyon,” that the Puritans had not separated from the Church of England, as the Pilgrims had before going to Holland. He found the Puritans not only not separated, but actually maintaining in America an established church supported by the civil state. Arrived at Nantasket on February 5, 1631, and at Boston a few days later, Roger Williams was welcomed as a “godly minister.” Still, he declined an invitation to join the congregation of the church at Boston as teacher, alleging two reasons, first, that “they would not make a public declaration of their repentance for having communion with the churches in England while they lived there,” which would be tantamount to a declaration of separation, and, secondly, that the civil “magistrate might not punish the breach of the Sabbath …. as it was a breach of the first table.” The latter refers to the classification of the Ten Commandments into two groups, one dealing with man’s relations to God, and the other with man’s relations to his fellowmen, to wit, the last six commandments. Roger Williams, in his denunciation of the prerogative assumed by the civil magistrate to punish for offenses against religion not amounting to a breach of the peace, had already attained to understanding of fundamental principles of religious liberty and of separation of state and church that have become American; and at the same time had marked himself for that persecution by the Puritan theocracy that reached a climax in Massachusetts in the edict of banishment pronounced against him in 1635, and that followed him thereafter so long as he lived. The edict of banishment has never been repealed;[2]Massachusetts rejected bills to repeal it, 1774, 1776, 1900, 1929. nor has Massachusetts ratified the first amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which embodies the doctrine of Roger Williams. The persecution was begun almost immediately; its persistent pursuit was far too relentless and too vindictive to make tenable claims by apologists for Massachusetts that the offense of Roger Williams was not principally so much religious as political and economic. As a matter of fact, the conflict between Roger Williams and Massachusetts was religious, so far as it involved fundamental questions of doctrine; was political, so far as he challenged the theocratic union of civil and religious agencies, civil support of religion, and misuse of the power of the state to enforce religious discipline; and economic, so far as he became an obstacle to the plans of the theocracy to bring all of New England under its control, with the magistrates-ministers in Boston as rulers.

Invited by the church at Salem to become an assistant to the minister, Roger Williams accepted, in spite of a protest to the Salem church from the Puritan magistrates at Boston, but continued for only a few months because of the persistent objection of the lord brethren. With his wife, Mary Barnard, who had emigrated with him on the ship “Lyon,” he removed to Plymouth, and there for two years was an assistant to the minister of the church. During that period he established a firm and enduring friendship with Massasoit, Chief Sachem of the Wampanoag Indians, and with the warriors of the tribe and of the Narragansetts, who later, during King Philip’s war, refused to molest Roger Williams when he ventured among them, although they burned the town of Providence. Equally firm and lasting were friendships with Canonicus and Miantonomah, Chief Sachems of the Narragansett Indians. Roger Williams was the intermediary passing between Massasoit and Canonicus and ending an old enmity that had estranged the sachems. Visiting the Indians frequently, Roger Williams laid the foundation for that knowledge of the Indian language which enabled him later to write and publish his “Key to the Language of America.” Roger Williams was a gifted linguist; besides being a proficient stenographer, he knew Latin, Greek and Hebrew, of ancient languages, and English, Dutch and French, of vernacular languages. While in England, 1651-1654, he exchanged the reading (or translation) of languages with John Milton, and gave lessons in languages to sons of a member of Parliament, to earn money to defray his expenses. He employed “the objective method, by words and phrases used colloquially, as distinguished from the analytic method of the ordinary grammars.” While at Plymouth he continued to exercise the propensity for argument and discussion that was characteristic throughout his life, and wrote a treatise on the royal patent, in which he maintained the thesis that the title to land in America could not be acquired through grant from the King of England, but only through purchase from the Indian owners settled on the land. This distinction between sovereignty and ownership became a settled conviction with Roger Williams, and explains the infinite care with which later in Rhode Island he conducted transactions with the Indians involving titles to land. It is also the accepted doctrine of modern international law, to wit, that a change of sovereignty does not affect the title to land, which continues in the original owners, and may be taken from them only by purchase by individuals, or by due process of law and with just compensation in the exercise of eminent domain.

Recalled to the Salem church as assistant minister in 1633, and chosen its pastor in 1634, Roger Williams found himself almost continually subjected to inquisition by the Boston authorities, civil and religious. He was called frequently to answer charges against him; that he gave ample cause therefor is true if it be admitted that Roger Williams was wrong, and that the Puritans were right; and there is no doubt that Roger Williams was obstinately opinionated and loved argument. Others who incurred the displeasure of the magistrates were silenced or banished; Roger Williams continued to be an outspoken advocate of truth as he saw the truth. So early as 1631 the General Court had limited freemanship (or citizenship) to members of churches, which involved the rejection of all not of the Puritan communion, and effectually reduced the number of freemen to a small fraction of the population, in 1634 a more drastic oath of fidelity to the government was prescribed. Perhaps it was this oath that precipitated William Blackstone’s decision to remove from Boston. Roger Williams raised the question as to the right to administer an oath to a sinful man, on the ground that he and the officer administering the oath were thus induced to take the name of God in vain. It was his general opposition to oaths in any form, quite as much as the Quaker attitude, that induced the form of civil engagement, originating in Rhode Island, by affirmation instead of oath if preferred. The persecution of Roger Williams continued. Along with other things of a trivial nature, yet magnified by those who sought his ruin, he was accused successively (1) of denying the validity of land titles based upon the royal patent, (2) of denying the right to engage a sinful man by oath, since the oath became a violation of the commandment as a taking of the name of God in vain, (3) of denying the right of the civil authority to punish offenses against religion not amounting to disturbances of the peace, and (4) of appealing to the people of other churches than those at Boston and Salem to join with him in protest against the action of the General Court, then controlled absolutely by the Puritan zealots. When the town of Salem petitioned the General Court for land at Marblehead belonging to the town, the petition was denied solely because of the alleged contempt of the church at Salem in engaging Roger Williams as minister and in retaining him in opposition to the known wishes of the Boston Puritans! Thus the civil authority in the General Court maintained (1) a right to identify the civil agency of town with the ecclesiastical agency of church, and (2) undertook to coerce the ecclesiastical agency by refusing justice to the civil agency. There could be no clearer definition of the issue of Theocracy vs. Democracy, and the case is stated with Theocracy as plaintiff and Democracy as defendant because the former was aggressive in its purpose to overawe and crush opposition and to establish itself firmly. On October 1, 1635, Roger Williams was formally exiled, the edict of banishment reading thus:

Whereas, Mr. Roger Williams, one of the elders of the church at Salem, hath broached and divulged diverse new and dangerous opinions against the authority of the magistrates: has also writ letters of defamation, both of the magistrates and churches here, and that before any conviction, and yet maintained the same without any retracting; it is, therefore, ordered that the said Mr. Williams shall depart out of this jurisdiction within six weeks next ensuing, which, if he neglect to perform, it shall be lawful for the Governor and two of the magistrates to send him to some place out of this jurisdiction, not to return any more without license from the court.

The edict of banishment subsequently was modified to permit Roger Williams to remain at Salem until spring, but the fear that he was still actively engaged in converting adherents to his cause, and the rumor that he planned to establish another colony as a refuge for the oppressed and persecuted induced the magistrates to summon him to Boston, in January, and on his failure to appear before them to send a posse to Salem with directions to seize Roger Williams and place him on board a ship for return to England. Roger Williams anticipated the arrival of the posse by three days, leaving his family which consisted then of his wife, a child born at Plymouth and a newborn infant, and departing whither no one at Salem would tell Captain Underhill, who commanded the posse and who had been entrusted with the execution of the sentence. Whether Roger Williams journeyed by boat or overland from Salem is not known; the location of Salem north of Boston, and the open water of Massachusetts Bay, through which a boat might make its way south to Plymouth or to some harbor close to the winter quarters of Massasoit, suggested that the flight had been by water. Roger Williams did not go to Plymouth, however; it appears to be doubtful that Plymouth would offer him a refuge under the circumstances. He made his way to the winter villages of friendly Indians, and passed fourteen weeks “storm tossed,” as he described the journey, in the wilderness. He visited Massasoit, and received a friendly welcome from the Chief Sachem. He purchased from Massasoit, either at this time or in 1635, land for a home and farm, and early in the spring had reached the easterly bank of the Seekonk River within what is now the town of East Providence, and began to erect a house and to plant. The news of his activity reached Plymouth, and he was requested by Governor Winslow of the Plymouth Colony, the westerly line of which extended to the Seekonk, to remove therefrom, lest a location within the Plymouth Colony affront Massachusetts. Roger Williams thereupon abandoned his farm, and made the trip down the Seekonk River which brought him to Providence. From the Slate Rock on the westerly shore of the river he was hailed by Indians with the greeting “What cheer, netop?” Concerning this phase of the journey of Roger Williams there is doubt and disagreement, particularly with reference to the party with him. Five persons, William Harris, John Smith, Francis Wickes, Thomas Angell, and Joshua Verein, joined Roger Williams either at the plantation begun east of the Seekonk or very soon after the arrival at Providence, and with Roger Williams constituted the six original settlers. Joshua Verein was the latest arrival. Of the others Roger Williams said subsequently “Yet out of pity I gave leave to William Harris, then poor and destitute, to come along in my company. I consented to John Smith, miller at Dorchester (banished also), to go with me, and at John Smith’s desire, to a poor young fellow, Francis Wickes, as also to a lad of Richard Waterman’s. These are all I remember.” The “lad of Richard Waterman’s” was Thomas Angell, who was believed by some writers to be the only companion actually with Roger Williams on the first trip to Providence. Roger Williams purchased land from Canonicus and Miantonomah, Chief Sachems of the Narragansett Indians. Other white men from Massachusetts and Plymouth joined the new settlement. In a deed of the land purchased from the Indians Roger Williams named twelve others as with him the thirteen original proprietors of Providence Plantations: Stukely Westcott, William Arnold, Thomas James, Robert Cole, John Greene, John Throckmorton, William Harris, William Carpenter, Thomas Olney, Francis Weston, Richard Waterman, and Ezekiel Holyman. John Smith had died; Joshua Verein had returned to Boston; Francis Wickes and Thomas Angell were still minors when this deed was written in 1638. This was the beginning of a migration from Massachusetts; not all of those who became discontented with the arbitrary tyranny of the Puritans came to Rhode Island. Thomas Hooker led some 800 to the Valley of the Connecticut River in 1636, who settled at Hartford, Windsor, Wethersfield and Springfield. Out of the union of the first three towns, which were not within the territory covered by the Massachusetts patent, as Springfield was, came the state of Connecticut, first organized as a commonwealth under Fundamental Orders, still displayed to visitors to Hartford as the first constitution adopted in the United States. Hooker in a sermon preceding the adoption of the Fundamental Orders had uttered the principle of government with powers restricted by fundamental law.

Anne Hutchinson at Pocasset

Roger Williams was scarcely settled at Providence before a fresh controversy arose in Massachusetts over the alleged heretical teachings of Mrs. Anne Hutchinson, wife of William Hutchinson. Anne Hutchinson, born Anne Marbury was a skillful nurse and had so much knowledge of medicine that she is sometimes referred to as a physician. She was a brilliant woman, with charm of manner, marked personal magnetism, and ability for discussion that captivated her disciples and confounded her opponents. She started the first home classes for immigrant women[3]A term applied recently (1926) to classes in their homes for illiterate women unable to attend classes in schools. in America. It was her practice to hold weekly meetings at her home, to which other women who could not, because of household cares and duties, attend the Sunday church meetings were invited to hear Mrs. Hutchinson relay the sermons. After a while men as well as women attended these meetings. So long as Mrs. Hutchinson was content to report without comment or criticism there appears to have been no disposition to interfere, but when she ventured to criticize the Sunday sermons preached by the ministers and to take issue with the preachers upon matters of doctrine, exactly that occurred which might be expected in a theocratic state rapidly tending to bigotry of the most intolerant type. Mrs. Hutchinson would have been dealt with immediately and summarily if she had not persuaded to her belief many of the most influential members of the community, including what gave promise of becoming an aristocracy of wealth in early Boston. The controversy of this period, which involved most of the Puritans of distinction enough to be named in history. is referred to as the Antinomian heresy, and suggests theological and metaphysical distinctions as to alleged covenants of grace and of works. The Puritan version of the Bible laid the foundation for the controversy in so far as a translator, seeking to emphasize the importance of the word “faith,” had rendered the word of Paul as “faith alone,” although the same version of the Bible carried the familiar quotation from James, “Even so faith, if it hath not works, is dead, being alone.” To the definition of metaphysics as “the attempt of one person to make another person who is not capable of understanding see clearly something which the person who is trying to explain it is himself incapable of understanding,” might be added the further suggestion of difficulties that arise when neither party to a controversy, in metaphysics or in any other field of science or philosophy, is willing to try to understand the position of the other party and each insists that the other party shall accept his own exposition. Anne Hutchinson preached the doctrine of justification by faith alone, or “inward light,” which had led some to style her the first Quakeress ; and accused her opponents, in their emphasis upon the covenant of works, of maintaining the doctrine of sanctification by works, or external evidence. It is evident that these seventeenth century controversialists had anticipated by almost three centuries the modern squabble between introspective psychologists and those who have chosen to follow the banner of stark realism in behaviorism. The issue, important as it must have been to the Puritans, and significant because it divided them ultimately into two hostile camps, out of which arose two religious sects almost immediately and others later, is vastly less important from the twentieth century point of view than were and are the consequences of it with reference to the state. Out of the controversy came the separation of Congregational and Baptist denominations in America, and the establishment of two new settlements in Rhode Island by emigrants from Massachusetts. Eventually the anti-Hutchinson party controlled the General Court, and on November 2, 1637, William Aspinwall, Deputy from Boston, was expelled from the court, and banished from Massachusetts. John Coggeshall, also from Boston, was expelled from the court, and disfranchised. Aspinwall and Coggeshall were among the founders of Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Reverend John Wheelwright was banished, with leave to depart within fourteen days; he established the town of Exeter, New Hampshire. William Balstone and Captain John Underhill were disfranchised and fined. Mrs. Anne Hutchinson was banished. Seventy-five freemen were proscribed on November 20, and ordered to deliver up their arms and ammunition unless they would retract or leave. The church confirmed and ratified the action of the General Court with reference to Anne Hutchinson by excommunication; the words of her condemnation were pronounced by Reverend John Wilson in March, 1638:

“Therefore in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and in the name of the church I do not only pronounce you worthy to be cast out, but I do cast you out, and in the name of Christ do I deliver you up to Satan, that you may learn no more to blaspheme, to seduce and to lie; and I do account you from this time forth to be a heathen and a publican, and so to be held of all the brethren and sisters of this congregation and of others; therefore I command you in the name of Christ Jesus and of this church as a leper to withdraw yourself out of the congregation.”

The Puritan theocracy, in the instance of Anne Hutchinson and others who had followed her in religion, had once more invoked the power of the state in a religious controversy, and the state had been made the too willing agent of the church. Again, as in the case of Roger Williams, the parties were Theocracy vs. Democracy; and again the champions of democracy withdrew from Massachusetts. While one may ponder what punishment might have been meted out to the opponents of Anne Hutchinson had she and her followers controlled the General Court, in view of the bitterness which was involved in the struggle, there is this much that may be written truly, that they, as freemen in Rhode Island, did sustain the doctrine of liberty of conscience, and that one of them, John Clarke, wrote the King Charles Charter of 1663, which guaranteed “full liberty in religious concernments.”

The defeated party had begun plans for emigration so early as the autumn of 1637. The leaders were John Clarke, a physician as well as a Baptist minister, newly arrived at Boston while the Antinomian controversy was at almost white heat, and William Coddington, third deputy from Boston to the General Court, which expelled William Aspinwall and John Coggeshall. Coddington, a rich merchant, was an adherent of Anne Hutchinson, but, though tried by the General Court, was adjudged not guilty. John Clarke arrived in Boston in November, 1637, and as he wrote in a pamphlet published in Rhode Island in 1651, and subsequently in London in 1652 under the title “Ill News from New England,” thought it strange to see that men “were not able so to bear with others in their different understandings and consciences, as in these uttermost parts of the world to live peaceably together.”[4]Compare the words used in the Charter of 1663 : “not being able to bear, in these remote parts, their different apprehensions in religious concernments.” He proposed migration, and to him and others was delegated the selection of a suitable place for founding a new colony. Moving to the north to escape the heat of the summer in Boston, the cold of winter was so severe, according to John Clarke’s narrative, “that we were forced in the spring to make toward the south. So having sought the Lord for direction, we all agreed that while our vessel was passing about a large and dangerous Cape [Cape Cod], we would cross over by land, having Long Island and Delaware Bay in our eye for the place of residence. So to a town called Providence we came, which was begun by one Mr. Roger Williams (who for matter of conscience had not long before been exiled from the former jurisdiction), by whom we were courteously and lovingly received, and with whom we advised about our design. He readily presented two places before us on the same Narragansett Bay, the one upon the main called Sowams,[5]Probably Warren or Bristol; Barrington, perhaps. The exact location of Sowams has been a matter of much controversy. the other called then Aquidneck, now Rhode Island. We inquired whether they would fall in any other patent, for our resolution was to go out of them all. He told us (to be brief) that the way to know that, was to have recourse unto Plymouth. So our vessel as yet not being come about, and we thus blocked up, the company determined to send to Plymouth, and pitched upon two others together with myself, requesting also Mr. Williams to go to Plymouth to know how the case stood. So we did, and the magistrates thereof very lovingly gave us a meeting. I then informed them of the cause of our coming unto them, and desired them in a word of truth and faithfulness to inform us whether Sowams were within their patent, for we were now on the wing, and were resolved, through the help of Christ, to get clear of all, and be of ourselves, and provided our way were clear before us, it were all one for us to go further off as to remain near at hand. Their answer was that Sowams was the garden of their patent, and the flower in the garden. Then I told them we could not desire it, but requested further in the like word of truth and faithfulness to be informed whether they laid claim to the islands in the Narragansett Bay, and that in particular called Aquidneck? They all with a cheerful countenance made us this answer: It was in their thoughts to have advised us thereto, and if the provident hand of God should pitch us thereon they should look upon us as free, and as loving neighbors and friends should be assistant to us upon the main.”

Roger Williams negotiated with the Narragansett Indians for a deed of Aquidneck, although he generously shared the credit for his success with Sir Harry Vane. Roger Williams, writing in 1658, said: “It was not price nor money that could have purchased Rhode Island. Rhode Island (Aquidneck) was obtained by love; by the love and favor which that honorable gentleman, Sir Harry Vane, and myself had with that great Sachem Miantonomah, about the league which I procured between the Massachusetts English, etc., and the Narragansetts in the Pequod War. It is true I advised a gratuity to be presented to the Sachem and the natives.” The deed was taken in the name of William Coddington and others, settlers, and dated March 24, 1638. It included Rhode Island and other islands in the bay except Prudence, the right of grass in the river and coves about Kickemuit and up to Poppasquash. On July 6 the settlers purchased wood and grass rights at Tiverton. A compact had been drawn up and signed by the settlers on March 7, 1638, and on the same day William Coddington was elected executive under the title “Judge.” The first settlement on the Island of Rhode Island was made at a place called Pocasset on the shores of the cove north of the village now called Newtown. That this site rather than the later location at Newport happened to be chosen is explained by the probability that the vessel carrying the larger number of settlers entered Narragansett Bay through the Seaconnet River, and sailed up, selecting the cove as the most feasible anchorage and landing place. The Aquidneck compact bears the signatures of William Coddington, John Clarke, William Hutchinson, Jr. (husband of Anne Hutchinson), John Coggeshall, William Aspinwall, Samuel Wilbur, John Porter, John Sanford, Edward Hutchinson, Jr., Thomas Savage, William Dyer, William Freeborn, Philip Sherman, John Walker, Richard Carder, William Balstone, Edward Hutchinson, Sr., Henry Bull and Randall Holden. The names of Thomas Clarke, John Johnson, William Hall and John Brightman also were signed, but bear erasure marks on the original document, which is in the Rhode Island archives in the possession of the Secretary of State. At the first town meeting held at Pocasset on May 13, 1638, William Coddington, William Hutchinson, John Coggeshall, Edward Hutchinson, William Balstone, John Clarke, John Porter, Samuel Wilbur, John Sanford, William Freeborn, Philip Sherman, John Walker and Randall Holden, the original thirteen at Pocasset, were present.

Newport Settled

The settlement at Pocasset grew rapidly as other disciples of Anne Hutchinson than those banished or disciplined withdrew from Massachusetts and followed her to Rhode Island. There were probably not less than 100 families at Pocasset in the first year of the settlement. Careful exploration of the island was made, disclosing the landlocked harbor at Newport, with possibilities for commercial development quickly recognized by the alert settlers, some of whom, including Coddington, were merchants, to whom farm life was irksome. On April 28, 1639, an agreement signed at Pocasset by William Coddington, John Clarke, Nicholas Easton, Jeremy Clarke, John Coggeshall, Thomas Hazard, William Brenton, Henry Bull and William Dyer witnessed their agreement to withdraw and found a settlement elsewhere on the island. Newport was chosen as the site for the new settlement. March 12, 1640, the two island settlements reunited, and the name Portsmouth was assigned to the plantation (Pocasset) at the north end of the island.

As Providence had been, and was still, Newport and Portsmouth also became havens of refuge for the persecuted from other New England colonies and from England and other parts of Europe. To Newport came the “Woodhouse,” the first Quaker ship, which landed eleven Quakers on the island. Thither also fled Obadiah Holmes from Massachusetts, after banishment, and from Plymouth, where he had established at Seekonk the first Baptist church in the Cape Cod colony. Of the original Pocasset and Newport settlers, and of those who came later, many departed for other places. William Hutchinson died in 1642, and his widow, Mrs. Anne Hutchinson, removed with his family shortly thereafter to a spot near Hell Gate at the western entrance to Long Island Sound. There she and the family were murdered by Iroquois Indians. Of the character and ability of Anne Hutchinson estimates of contemporaries vary with the bias of the period. Of later writers among even the descendants of the Massachusetts Puritans the opinion generally held is that she was a remarkable woman whose appearance in Boston happened at a period in which the town was psychologically prepared for the outburst which her teaching precipitated. Not all of the Puritans were ready to follow the leadership that was converting the government of the colony into an unbearable tyranny. Roger Williams and Thomas Hooker had left, each one to establish a democracy that approached nearer to the ideal that was to be American. In dealing with Anne Hutchinson and her followers, as with others before and after, the Massachusetts leaders assumed the position that religious freedom threatened the security of the state; it did seriously threaten theocracy. With the departure from the colony of one after another of the progressive spirits who might have saved it from madness, the control of the government of Massachusetts was strengthened for the megalomania that displayed itself in the frenzied fury of whipping heretics, hanging Quakers and burning witches, which ended only when the King of England, Charles II, intervened and forbade judicial murder in Massachusetts, 1661.

Samuel Gorton

A fourth settlement in Rhode Island was made at Shawomet, later called Warwick, by Samuel Gorton, sometimes called the Firebrand of New England, who purchased land from the Indians under a deed dated January 12, 1642-1643. Gorton arrived at Boston from England in March, 1637, and removed shortly thereafter to Plymouth. Scarcely a year had passed ere his views upon religion had occasioned a disturbance in Plymouth. Ralph Smith objected to Mrs. Smith’s attendance at religious ceremonies conducted by Gorton in the latter’s home, and sought to evict Gorton, who occupied part of a house owned by Smith. In the parallel case in Providence Joshua Verein was disfranchised temporarily for interfering with his wife’s liberty of conscience in attending religious ceremonies of her own choice. The outcome of the Gorton-Smith controversy in Plymouth is not clear from the record. Samuel Gorton was banished from Plymouth actually for open contempt of court in the process of defending Ellin Aldridge, a servant in his family, who was threatened with exile as a vagabond outcast because she had smiled in church. If Gorton did not display his contempt for the court and government at Plymouth in his arraignment of the judges, he made no serious effort to conceal it. The dignity of a court must be preserved even in a democracy.

From Plymouth Samuel Gorton removed to Pocasset; there he was one of those who signed an agreement to reorganize the body politic after the withdrawal of the Newport settlers, carrying with them officers and records, had destroyed for the time being the government existing under the compact signed at Boston. Gorton subsequently refused to become a party to the agreement of March, 1640, through which Newport and Pocasset, the latter under the name of Portsmouth, were reunited, and at that time raised a question as to the right of any group of settlers to establish a government without royal sanction. This issue of legitimacy was fundamental, involving as it did controversy that troubled Rhode Island for a generation, until, in 1663, King Charles II granted the royal Charter. Before the court at Portsmouth, this time defending another servant, who was charged with assault and battery, Gorton denied the court’s jurisdiction and constitutionality for want of royal authorization, alleging that none of the governments in Rhode Island had a legal foundation through relation to the crown.[6]For a discussion of this point, see Newport vs. Gorton, 22 R. I., 196. Again Gorton so conducted himself as openly to affront the court and incur punishment for flagrant contempt, not the least of his offenses including addressing the justices as just asses.” No court may admit its own incompetence to the extent of denying the validity of the government to which it owes its existence; a justice of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island remarked two and one-half centuries later in the course of a trial in which the constitutionality of the court itself had been questioned,[7]Floyd vs. Quinn, 24 R. I., 147. that “the court has no constitutional right to commit suicide.” Whether or not Gorton was whipped, a moot question for debate, he was ordered to depart from the Island of Rhode Island, and went, n maintaining that there was no legal establishment in Rhode Island Gorton had neglected the possibility that a de facto government may become de lege. There was no question of religion, and none of conscience involved in the Portsmouth trial.

Gorton went to Providence, and there he applied for reception as freeman and inhabitant. Both Roger Williams and William Arnold opposed the petition, because of the contempt for government which Gorton had expressed at Plymouth and at Portsmouth. Roger Williams was not willing to expand his insistence upon liberty of conscience and full liberty in religious concernments to the anarchy and chaos involved in the denial of civil government. His position on this issue was expressed clearly and masterfully in a letter written some years later:

There goes many a ship to sea, with many hundred souls in one ship, whose weal and woe is common, and this is a true picture of a commonwealth, or a human combination, or society. Both Papists and Protestants, Jews and Turks, may be embarked in one ship, upon which supposal I affirm, that all the liberty of conscience that ever I pleaded for turns upon these two hinges—that none of the Papists, Protestants, Jews or Turks be forced to come to the ship’s prayers or worship, nor compelled from their own particular prayers or worship, if they practice any. I further add that I never denied that, notwithstanding their liberty of conscience, the commander of this ship ought to command the ship’s course; yea, and also to command that justice, peace, and sobriety, be kept and practiced, both among the seamen and all the passengers. If any of the seamen refuse to perform their services, or passengers pay their freight; if any refuse to help, in person or purse, toward the common charge or defence; if any refuse to obey the common laws and orders of the ship concerning their common peace or preservation; if any shall mutiny, and rise up against their commanders and officers; if any should preach or write that there ought to be no commander because all are equal in Christ, therefore no masters or officers, no laws or orders, nor corrections nor punishments; I say I never denied but in such cases, whatever is pretended, the commander or commanders may judge, resist, compel, and punish such transgressors according to their deserts and merits.

Gorton and his followers continued in Providence until the resistance of one of them to the service of court process distraining his cattle in civil proceedings arising out of a personal law suit produced bloodshed. They then withdrew to Pawtuxet and built houses. At Paw-tuxet events followed rapidly to produce the situation that preceded armed intervention by Massachusetts,[8]See Rhode Island Relations with Massachusetts and Connecticut. the arrest and trial of Gorton in Massachusetts, and treatment of Gorton by the Massachusetts authorities which made him, now a martyr suffering in a common cause, beloved of Rhode Islanders because of his treatment by the common enemy, and because of his subsequent contribution to the strength of colony and state. Gorton and his followers removed from Pawtuxet to Shawomet, the purchase of which included the territory now occupied by the towns of Warwick, West Warwick and Coventry. Gorton in later years was a constructive, though always belligerent, participant in public affairs.

Later Settlers

No list of settlers in Rhode Island would be complete that did not include all of those who have come through three centuries, for Rhode Island is still in the twentieth century a frontier state in its work of absorbing immigration attracted hither by the broad liberality of public life and opportunities for employment. It remains at this time to mention, following the settlement of the four original Rhode Island towns, other earlier settlers and settlements that were not merely extensions of the original communities. Westerly, the fifth Rhode Island town to be incorporated, was settled by Newport people, drawn thither by the advantageous situation with reference to the Pawcatuck River and Little Narragansett Bay. The Island of Manisses, called Louisa by Verrazzano and Block Island by the Dutch rediscoverer, was taken by Massachusetts as spoils of conquest in the Pequot War, and granted on October 19, 1655, to John Endicott and others, who sold it to a land company. Settlement was begun in 1662, the party proceeding from Boston to the Taunton River, through which and Mount Hope Bay, and Narragansett Bay they sailed out to the island. A granite monument marks the spot near which these pioneers made their landing and began their plantations. Block Island was included in Rhode Island as described by the Charter of 1663, and was incorporated as a town under the name of New Shoreham in 1672.

In the Narragansett country, a name applied in colonial days to approximately all of Washington County, and part of Kent County, trading posts were established by the Dutch at an early period. Richard Smith, originally from Gloucestershire, England, but directly from Taunton, established a trading post at what has since been known as Wickford. The lumber for the house was transported by ship from Taunton. Near Smith’s trading post Roger Williams also maintained a trading post for a few years, eventually selling out to Smith his “trading house, two big guns and a small island for goats.” Richard Smith leased land from the Indians in 1656 for sixty years; in 1659 for 1000 years; and in 1660 obtained title in fee simple by quitclaim deed of the reversion. Randall Holden and Samuel Gorton bought Fox Island and a neck of land near Wickford in 1659. The Atherton purchase of a large part of the Narragansett country, made in violation of law, was one source of friction between Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts, all rival claimants.[9]See Rhode Island Relations with Massachusetts and Connecticut. When Walter House was killed by Thomas Flounders, inquests were conducted by both Rhode Island and Connecticut officers. The territory was organized as a Rhode Island town under the name Kingstown in 1674.

What promised to be a flourishing French Huguenot settlement at Frenchtown in East Greenwich failed because title to land was found to be defective, and settlers were dispossessed. In October, 1686, a number of French Huguenots purchased in London from the Atherton Company a tract of land in the Narragansett country, described as all of what is now the part of Rhode Island west of Narragansett Bay and south of the old town of Warwick. Forty-eight Huguenot families, then refugees in London, were to receive under the contract of purchase 100 acres of upland each, and a share of meadow land. They came originally from La Rochelle, Saint-Onge, Poitou, Guyenne, and Normandy. Prominent members of the group were Ezechiel Carre, their pastor; Pierre Ayrault, a physician, and Pierre Berthon de Marigu of Poitou. Arrived at Frenchtown, the settlers began building shelters against the coming winter. They worked rapidly, and before the cold weather set in had put up about twenty houses, and a few cellars or dugouts were completed. The dugouts, prepared by those who intended to put up durable houses in the following summer, were square pits, about seven feet deep, floored and walled with wood, and roofed with logs and layers of turf. There was nothing pretentious about these little temporary homes, but they were comfortable and kept out the cold. While waiting for the spring farming season to open, the Huguenots busied themselves with clearing their acres of stones, cutting out trees and brush and otherwise preparing the fields for cultivation and planting. Fifty acres of land were set off for the maintenance of a school, and 150 acres were donated to pastor Carre for his support, and plans were made to build a church as soon as weather conditions would permit.

When the spring season opened the Huguenots went to work with zeal, and it was not long before what had been a wilderness was a veritable garden. Diligence was observed, the cellars or dugouts gave way to substantial buildings, and where the virgin forest had been, now were orchards and vineyards. About the homes were hedges, fences and attractive lower gardens, the seed for which had been brought from Europe by the women of the colony. Skilled in grape cultivation, some of the East Greenwich Huguenots raised a variety from which superior wine was made. Others turned their attention to the planting of mulberry trees, int3eding to establish silk raising, spinning and weaving as a permanent industry.

They believed that it would not be many years before large numbers of experienced silk spinners and weavers would come from the old country and set up at Frenchtown the center of the silk business of the new country. It was a beautiful dream, the realization of which doubtless would have made that part of Rhode Island enormously wealthy. But the dream did not prove to be true. Within five years from the day of their arrival at Frenchtown only two Huguenot families remained. The Huguenots, innocently, had settled on land to which others held claims antedating that of the Atherton Company. One by one the Huguenots were dispossessed of lands which they had cleared and cultivated. In 1691 the settlement was abandoned. The story of Frenchtown awaits a poet who can weave into epic verse a tale of Acadian simplicity, reminiscent of Longfellow’s “Evangeline.”

Gabriel Bernon, another Huguenot, came to Newport in 1695, and later to Providence. He was largely instrumental in building Trinity Church in Newport; St. Pauls Church in Kingstown, and St. John’s Church in Providence, the first three Episcopal churches in Rhode Island. He was buried in St. John Churchyard, Providence, in which a tablet preserves his memory. One of his daughters married Chief Justice Helme of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island, 1767-68. The second wife [10]His first wife, “The Star of La Rochelle,” by Elizabeth Nichols White. of Gabriel Bernon was Mary Harris, granddaughter of William Harris, that one of Roger Williams’ loving companions who was engaged in law suits with Williams covering a long period of years.

Barrington, 1660, Bristol, 1680, and Little Compton, 1674, held by Massachusetts until 1742 in spite of the clear purport of the definition of boundaries in the King Charles Charter, were settled by Pilgrims from the Plymouth Colony. The names of early inhabitants of these towns include the family names of many who afterward were prominent in the history of Rhode Island. The peninsula at Bristol was sold by the Plymouth Colony to John Walley, Nathaniel Byfield, Nathaniel Oliver and Samuel Burton for £1100, the price indicating the value placed upon this location by the Pilgrims, who planned to make Bristol the seaport of Plymouth Colony. Benjamin Church, the same Captain Benjamin Church who won renown as a resourceful commander in wars with the Indians, was invited by John Almy to visit Little Compton in 1674, and purchased land there with the purpose of settlement. Almost immediately thereafter came the beginning of King Philip’s War and work elsewhere for the Captain, which suggested postponement of the homebuilding project. Other early settlers at Little Compton included Elizabeth Alden Peabody, much better known as Betty Alden, and her husband, whom Roswell B. Burchard, who married a descendant of Captain Church and was later Lieutenant Governor of Rhode Island, styled a man honored principally because of his wife. Elizabeth Alden Peabody was born Elizabeth Alden, child of John Alden and Priscilla Mullin, whose romantic love story Longfellow immortalized in the Courtship of Myles Standish.

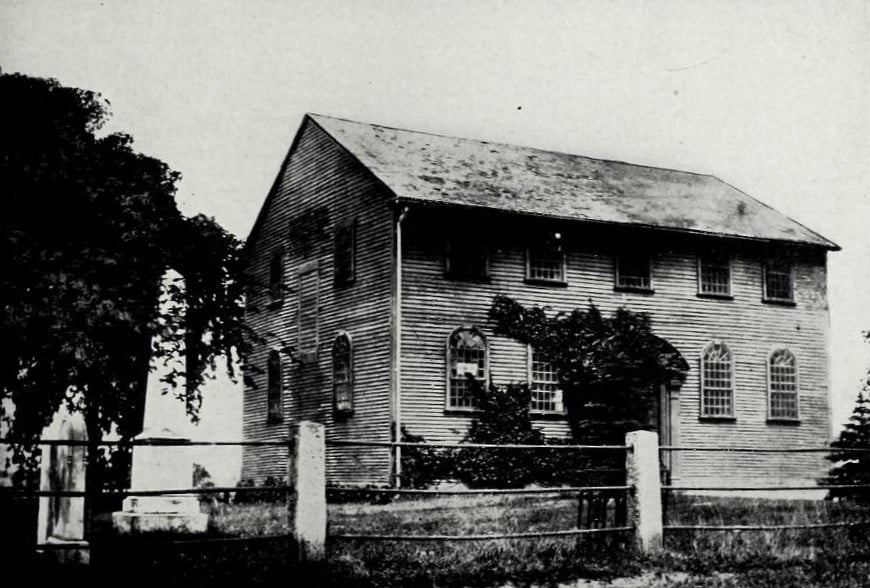

Of the Dutch who built trading posts for traffic with the Indians and who were also parties to a profitable trade with the people of Rhode Island during the period in which ill feeling with neighboring colonies prevailed, little trace remains save the fact that many place names were established by the maps published by the Dutch geographers, including possibly the name of the State of Rhode Island. Some of the Dutch traders remained in Rhode Island after the English had taken Manhattan and renamed New Amsterdam as New York, and intermarriages resulted. Many of the followers of Anne Hutchinson subsequently became Baptists, no doubt because of the teaching and preaching of John Clarke; and many others became Quakers, the name commonly given to members of the Society of Friends. Quakers were received cordially in Rhode Island, though dealt with summarily in Plymouth by whipping and banishment, and in Massachusetts by scourging, branding, torturing, cutting off of ears and hanging. Roger Williams had no sympathy with the doctrines of the Quakers, as witness his journey to Newport when over seventy years of age, paddling his own canoe through nearly thirty miles of open water, to debate with George Fox “fourteen points”[11]Rhode Island anticipated Woodrow Wilson’s “fourteen points.” involving questions of dogma. Subsequently Roger Williams published the pamphlet entitled “George Fox Digged Out of His Burrowes.”[12]Fox’s answer: “A New England Firebrand Quenched.” But drastic as he was in condemning the doctrines of the Society of Friends, and caustic as was the language which he hurled at their leader, Roger Williams would not acquiesce in measures to exclude Quakers from Rhode Island or to interfere with them otherwise merely for entertaining their beliefs and for practicing the rites of their religion.[13]See Rhode Island Relations with Massachusetts and Connecticut. The Society of Friends erected the first meeting house at Portsmouth, and the Quakers subsequently furnished a long line of distinguished Rhode Islanders, including several who became Governors.

Hebrews, who were tolerated in few Christian countries in the seventeenth century, began to settle in Rhode Island so early as 1655, coming some from New Amsterdam and from Curacoa, both Dutch, and others directly from Holland. Rhode Island’s toleration was broad enough to embrace Hebrews as well as Christians of all denominations, and the Rhode Island Hebrews of the seventeenth century became the nucleus for an influential community. The liberality of Roger Williams appears in his proposition while in England in 1654, “whether it be not the duty of the magistrate to permit the Jews, whose conversion we look for, to live freely and peaceably amongst us,” and his plea: “Oh, that it would please the Father of Spirits to affect the heart of the Parliament with such a merciful sense of the soul-bars and yokes which our fathers have placed upon the neck of this nation, and at last to proclaim a true and absolute soul-freedom to all the people of the land impartially, so that no person shall be forced to pray nor pay otherwise than as his soul believeth and consented.” As for England there was hope in the famous Declaration of Breda made by Charles Stuart, who was to be Charles II, in anticipation of his return to the throne of his father.

Governor Peleg Sandford of Rhode Island, writing from Newport, May 8, 1680, answering a questionnaire sent out by the British Board of Trade, said: “Those people that go under the denomination of Baptists and Quakers are the most that publicly congregate together, but there are others of divers persuasions and principles all which together with them enjoy their liberties according to his majesty’s gracious Charter to them granted, wherein all people in our colony are to enjoy their liberty of conscience provided their liberty extend not to licentiousness, but as for Papists, we know of none amongst us.”

Truly the spirit of Roger Williams had entered into Rhode Island.

Source: Carroll, Charles. Rhode Island: Three Centuries of Democracy; vol 1 of 4. New York: Lewis historical Pub. Co., 1932.

References

| ↑1 | January, 1626, Julian calendar, old style; January, 1627, Gregorian calendar, new style. The Gregorian calendar made January, instead of March, the first month. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Massachusetts rejected bills to repeal it, 1774, 1776, 1900, 1929. |

| ↑3 | A term applied recently (1926) to classes in their homes for illiterate women unable to attend classes in schools. |

| ↑4 | Compare the words used in the Charter of 1663 : “not being able to bear, in these remote parts, their different apprehensions in religious concernments.” |

| ↑5 | Probably Warren or Bristol; Barrington, perhaps. The exact location of Sowams has been a matter of much controversy. |

| ↑6 | For a discussion of this point, see Newport vs. Gorton, 22 R. I., 196. |

| ↑7 | Floyd vs. Quinn, 24 R. I., 147. |

| ↑8, ↑9, ↑13 | See Rhode Island Relations with Massachusetts and Connecticut. |

| ↑10 | His first wife, “The Star of La Rochelle,” by Elizabeth Nichols White. |

| ↑11 | Rhode Island anticipated Woodrow Wilson’s “fourteen points.” |

| ↑12 | Fox’s answer: “A New England Firebrand Quenched.” |

Informative. An interest in the early settlers to Newport Rhode Island 1638. My Mothers maiden name was Cotterell born 1920. Her fathers spelling of the surname. Her Grandfathers spelling of the surname was Cottrell. I see a Nicholas Cottrell sailed to Newport Rhode lsland 1638